At the Domesday Survey of 1086 Waltham Abbey’s Upminster manor was made up of the Abbey’s estate of around 340 acres, with another 1,200 acres of so of woodland. The male tenant population of 13 had four ploughs between them to carry out their obligations to work on the Lord’s land. These tenants were split into three categories: there were six “villeins”, who held the largest plots, possibly up to 30 acres, four “bordars” each with a smaller holding – perhaps five acres or so – and three “serfs” who either held a small plot of land, or none at all. The survey also recorded a “sokeman” – a tenant free of working on the Lord’s land – who held 30 acres and half a “carucate” (a ploughland – possibly around 60 acres).

For some time after Domesday, it’s likely that the manorial tenants continued to have a duty to work on the lord’s estate for a certain number of days each week. At some stage this obligation was replaced by a money payment called a quit rent, usually in proportion to the size and value of a tenant’s holding. These quit rents probably remained unchanged from the time they were fixed in the Middle Ages, so over time they declined in relative value due to inflation. The earliest list of the manorial tenants dating from 1684 shows 15 occupiers assessed for quit rents totalling £7 13s 1½d annually. Four of these tenants, who occupied the larger farms, paid just over one pound each, five paid between 8 shillings and 15 shillings each, with the remaining seven each paying 6 shillings or less. Lists of the manor’s quit rents in the late Victorian period show that these amounts were still the same 200 years later.

The manor’s business with its tenants was carried out in the manor court baron, which usually only met from time to time when there was business to conduct. Although they were called “tenants”, occupiers could in fact sell their land or properties and when they died bequeath ownership to their heirs. The manor court had formal procedures which required a property to be surrendered “into the Lord’s hands” and then granted to the new tenant. This was set down in the records of the manor court, known as the court rolls or court books, depending on the way they were kept. The new property owner received a copy of the court roll entry, which became their evidence of title, leading to this form of tenure being known as “copyhold”. This probably came into being from the mid-14th century and would have accelerated after the Black Death.

The new owner paid a series of fees covering every step of the process from the clerk’s fee for writing the entry, a charge for the parchment it was written on and a fee for the crier who made a proclamation before the court. Typical fees to Upminster Hall manor in the late 17th century were up to £4 for copyhold properties changing hands. For larger properties the Lord also had the right to claim the tenant’s best beast or to levy another fine known as a heriot; over time this fee also became a fixed monetary payment, usually around £5 or £10 for the largest Upminster properties, quite a significant sum.

The surviving series of manor court records for Upminster Hall manor at the Essex Record Office run from the 1650s until the manor court was dissolved in 1936, with some limited records surviving from the 16th century when the manor first passed into private ownership. In addition, these court records are supplemented by surviving records of the granting of copyholds for some properties.

The copyholders could convert their holding to freehold (called enfranchising) by paying a one-off fee to the Lord of the Manor, which was usually (but not always) registered in the manor court records. Where the Lord of the Manor bought a property this extinguished the copyhold status and it could then be leased out to tenants or added to other adjacent properties already leased out to form a larger farm. The Lord’s income from leased properties far exceeded the quit rents and heriots. From 1852 the Copyhold Acts provided a legal basis for tenants to “enfranchise” their property, and there are several such records for Upminster Hall in The National Archives.

Although the relative money value of copyhold quit rents and heriots fell, the Lord’s income from leaseholds rose over time, as the rent was reviewed each time the term of the lease expired. Villagers were also allowed by the Lord to enclose small parts of the roadside manorial waste and erect cottages, which generated additional quit rents to the Lord of the Manor. The north side of Cranham Lane (now St Mary’s Lane), for instance, between Cosy Corner, at the main cross roads to the Cranham boundary, was progressively enclosed in this way during the 18th century while other encroachments from the road side waste were permitted in Bird Lane and close to Upminster Common. The annual quit rents for such small enclosures ranged from one to five shillings per property.

The property names recorded in the manorial court were usually the ancient names by which the holdings were known. Over time, smaller plots were combined to form larger farms which often became known by the name of a later tenant. By 1727 Great Tomkyns Farm comprised four separate areas totalling 82 acres. Around half was the area around the farmhouse (39 acres) west of Bird Lane, sometimes called Fortys in manor records, plus two fields named Great and Little Sockets (10 acres) east of Bird Lane and south of Warley Hill which the earliest records call Stockett and Stockett Mead alias Browns. A detached area of 25 acres, north of Tylers Hall Farm and east of Nags Head Lane, was called Holmans in the manor courts after an owner in 1413, but known by the owners as Further Grounds. All of these were copyhold properties, each separately heriotable, so on each occasion that Tomkyns changed hands there were heriots of £25 to pay to the Lord of the Manor. Tomkyns also included a nearby freehold field of 10 acres variously called Howlins or Holdens (Haldens in earlier records). Similarly, Ivy Lodge Farm seems to have been assembled from several small closes called Warrens, Ryddens & Pannells Croft and Hodges. Beacon Farm, a small farm close to the Four Wantz junction was known as Stretman’s in the court records, although the name of the adjacent Poddies Farm, after an occupier named Poddy, remained unchanged from the late 17th century.

We now turn to the Lord of the Manor’s own land holdings, his “demesne”. These comprised the lands which were those directly owned by Waltham Abbey before the Dissolution, supplemented by any later local farms bought in.

From a description in 1702, and other similar listings over the next decade, this demesne amounted to around 500 acres in all, in three separately identified holdings. By 1842, the Lord, Champion Edward Branfill, was farming 354 acres of his own land directly, with 225 acres leased to farmers and other tenants, within the manorial area of Upminster Hall, as well as 94 acres west of Hall Lane, within the Manor of Gaynes.

In 1702 the first and largest of these areas made up of some 190 acres east of Hall Lane and to the north and south of Upminster Hall. This comprised a meadow called Conduit Mead (still bearing this name in 1842), an adjacent meadow called Little Crouchfield, two meadows behind the Hall, a close called “Barnefield” (presumably by the current “Tithe” Barn Museum), closes called Peaseshott, Callvefield (Culvers Field in 1842), Shutleaze and two closes called Leylands. In 1842 Champion Edward Branfill farmed an equivalent area of around 110 acres so the much larger original holding probably included the other fields directly to the north, part of his leased out Potkiln Farm.

The second area was on the opposite (west) side of Hall Lane, running down to the River Ingrebourne. This included three closes named Millfield (which were still called Upper and Lower Mill Field in 1842), three closes named Cowdowns and a parcel named Cowdowns Mead, two parcels called River Meadow (the same name in 1842), a parcel of meadow called French Mead, a parcel of “Stubbed” land, and two closes called Grovefield and Great Grovefield, an area of 210 acres compared. In 1842 Branfill farmed an area of 170 acres west of Hall Lane in 1842 while the area adjoining this to the north and along the Ingrebourne totalled another 50 acres

The reference to Millfield is interesting: at face value it may suggest that a mill was previously located here, favourably sited for the south westerly winds from across the Ingrebourne valley. If so, there is no record of a mill in this location survives – this would have pre-dated the mill on Upminster’s Gaynes Common, originally erected in the mid-17th century. This field has been developed as Spenser Crescent.

The third area lay south of Upminster Hall, down to Cranham Lane. In 1702 this included two closes called East Crouchfield and Middle Crouchfield totaling 70 acres and a 32-acre field named Great Crouchfield. In 1571 this area had been excluded from George Wiseman’s lease of Upminster Hall and it was described as “Le Crouchefield” (50 acres) and “Eche Crouchfield” (60 acres). By 1842 these names had been corrupted to “Church Field”. These fields totalled 109 acres in 1842, similar to the corresponding demesne areas in 1571 and 1702.

Developments along what later became Station Lane nibbled away at the edges of the Branfill’s estate. In 1851 the Lady of the Manor granted the land for the new National School and in 1867 just to its south T L Wilson took out an 80-year lease for £5 a year and developed his new house and carpenters’ yard.

In May 1885 the coming of the railways to Upminster with the opening of the Barking to Pitsea route cut off the southern part of the Branfill’s Upminster Hall estate from the main part north of the new line. The station, sidings and goods yard were built on part of their estate. In 1886 Wilson’s former business partner William Hook and the dairyman Edwin Battson were granted 99-year leases on plots 200 feet by 70 feet, building two pairs of semi-detached properties south of what later became St Lawrence Road. Battson’s premises now survive as Costcutters and Caffe Nero, while Hook’s was on the site that housed Talbot’s garage and Martin’s Newspaper shop, but are now Roomes Furniture Store. As early as 1887 the Branfill family seem to have decided to dispose of the whole of the rest of the detached southern part, drawing up plans to lay out roads there, but nothing came of these proposals.

In March 1905 Arthur Williams, Director of Samuel Williams & Co of Dagenham Dock, who then lived at Hoppy Hall, leased from the Branfill family the northernmost plot of their estate on the west side of Hall Lane, named the Upper Eight Acres. Here Williams built his grand new home of Upminster Court, designed by the leading London architect and Upminster resident Charles Reilly, who lived at High House, nearly opposite the church in Corbets Tey Road. After Upminster Court was completed Williams bought the site from the Branfill Trustees in October 1907 for £3,000.

But the major change came in November 1906 when the southern 150 acres of the Branfill estate was sold for £20,000 to the developer Peter Griggs and his company W P Griggs and Co to develop their Upminster Garden Suburb there. Progress was rapid, with over 200 houses completed by 1911, north and south of the railway. Work continued throughout the Great War, although at slower pace, and after Griggs’ death in 1920 the successor company Upminster Estates Limited expanded the estate development beyond the initial footprint.

Very little of the original Upminster Hall estate now remains undeveloped for housing or retail uses. The largest area of green space now forms part of Upminster Golf Club, with the area between the Hall and Hall Lane (holes one and 18), and the much larger area to the west of Hall Lane (holes two to 17), running down to the River Ingrebourne. While the golf club website states that the eminent golf architect Mr Henry Shapland (“Harry”) Colt (1869-1951) was engaged to lay out this course, Upminster is not one of those officially listed as his design. A newspaper report of the opening refers to the club’s first professional F.C Plumbridge having provided “expert supervision” of building the course, transformed from a “barren and somewhat uninteresting tract of land … parts of which were sometimes waterlogged”. Play began on 26 May 1928, with W.G. Key, who was an instrumental figure in the club’s foundation ceremonially playing the first tee shot.

At present the Upminster Pitch and Putt course, bordered by The Fairway on the north, Holden Way to the east and Ingrebourne Gardens to the south, remains undeveloped, although Havering Council has recently approved the disposal of the site with outline planning permission for the development of 37 three-, four- and five-bedroom houses while retaining a significant area of public open space. This eight-acre site was originally set up as a private nine-hole golf course in the late 1920s in a field owned by Upminster Estates, originally named Dove House Mead. At the outbreak of World War Two this was acquired by the War Department for use as an assault course, with Hornchurch UDC buying the land at the end of hostilities. In 1950/51 an 18-hole short course was developed there, and a large pond on the eastern of the site was filled in by the estate developers.

Another large surviving area forms the major part of the 35-acre Upminster Hall Playing Fields, bought by the Hornchurch UDC in 1935. In the late 19th century, the six-acre area fronting Hall Lane, which was part of a 13-acre meadow named Walnut Tree in 1828 and Avenue Mead in 1842, had hosted at the northern end a cricket pitch and pavilion. This was the home ground of the Upminster Friars club, a gentleman-farmers team and was the site of the cricket legend W.G Grace’s visit to Upminster in May 1896. Grace became the Friars’ President and the portrait of himself that he presented to this club, which disbanded a few years later, passed to Upminster Cricket Club. The area of meadow was reinstated to grassland in 1957 when a football pitch was laid, but it is now used for more informal recreation.

The park is bisected by the remnants of what was once a triple avenue of walnut and chestnut trees. Originally a row of walnut trees was planted each side of two rows of chestnut trees, possibly as a weather protection but also forming a decorative addition to the landscape on the north-south ridge on which Upminster Hall stands. Although such an avenue may suggest a possible carriageway approach to the Hall, this stops at a field boundary without any obvious link to the main road. The walnuts were probably grown as a food crop and in October 1825 a gardener from Upminster Hall, named Clarkson, who was gathering walnuts from one of the trees died after falling from “a considerable height”.

This triple avenue, shown on Chapman & Andre’s 1777 map, was still considered “healthy and vigorous” in 1881, was largely intact in the late 1920s, and in 1951 could still be described as a “fine feature”. But in the decades since, trees from the avenue have progressively been lost and nowadays only a handful of these ancient chestnuts remain at the southern end, closest to the Hall.

In 1958/59 a further six acres to the east of this avenue of trees was levelled to form a hockey ground, which has in recent years been replaced by rugby and football pitches. The area to the east of the avenue was originally traversed by the tramway which ran south from the brickworks to Upminster station. During dry summers this tramway route, which continues south along the borough boundary at the rear of the gardens of houses on the east side of Holden Way, can sometimes still be seen as marking in the grass or in aerial photos. To the furthest eastern part of the park the vestiges of the ancient boundary between Upminster and Cranham, which runs diagonally across the south-eastern corner, can still be seen, running from the Cranham Health Centre to the tramway route. The south-eastern part of the park in Cranham was formerly part of Dorkins Farm.

This is the third and final article about Upminster Hall, the others being:

For enclosures along Cranham Lane (now St Mary’s Lane) see also

- St Mary’s Lane, North Side Part 1: from the Cranham boundary to Garbutt Road

- St Mary’s Lane, North Side Part 2: from Garbutt Road to the Cosy Corner Crossroads

Main Archive Sources

Essex Record Office:

- Manor of Upminster Hall – Court Books 1653-1936 – D/DEc 9/1 – 5

- Deeds of Upminster Hall 1686 – 1711 – D/DM T83

- Deeds of Upminster Hall 1686 – 1701 – D /DCq T1

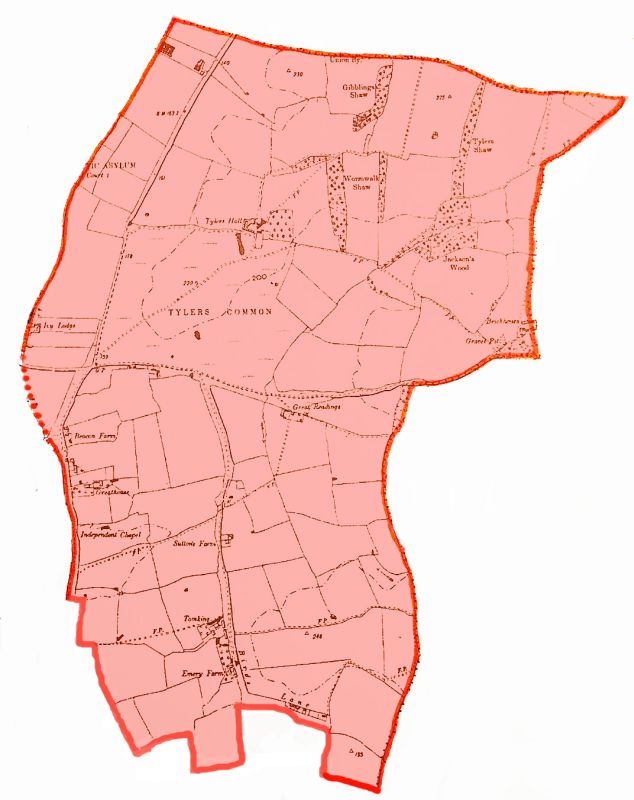

- Map of Upminster Hall Manor 1828 – D /DRu P3

- Rentals of the Upminster Hall Estate 1870-1890 – D /DU 1330/2

- Stewards Fee Book 1773-1793 – D/DEc 9/11

- Sale Catalogue – Upminster Hall: 1927 SALE/A421

The National Archives:

- Deeds and awards of Enfranchisement Files MAF 9/99/70-80

Main Printed Sources:

The Upminster Local History Group: The Story of Upminster: Book 4 People of the Middle Ages (1958)

The Upminster Local History Group: The Story of Upminster: Book 5 The Branfills of Upminster Hall (1958)

Thomas Lewis Wilson Sketches of Upminster (1856) pp110-115

Thomas Lewis Wilson History & Topography of Upminster (1881) pp31-38, 182-189

Tony Fox Upminster Hall, its barn and estate (2002)

W.R. Powell “Upminster” in A History of the County of Essex: Vol 7 (1978) pp.143-163

P.D.A Harvey Manorial Records (1984)

Hornchurch Urban District Council Report on parks and recreation grounds September 1961 (Havering Local Studies ref LC711.558)

Upminster Golf Club: The first fifty years (1928-1978)

Upminster Cricket Club 1858-1958: History and Centenary Programme

Thank you very informative

Glad you enjoyed it.

Fascinating. Can’t get enough of our local history.Thank You.

Many thanks! Much appreciated.

Very much enjoyed your article, thank you for sharing

Thanks for your comments!

This is an absolutely fascinating piece of work. It must have taken you ages to compile! Many thanks indeed.

Fred

Thanks!

Very interesting article, thank you. On Google Maps’ current satellite image of the playing fields, the old tramway is quite obvious across the grass. It’s amazing how something no longer there can have such a continuing effect on the landscape.

Thanks for your comments. The route followed old field boundaries in places, which often remain for many years afterwards.

Pingback: The Branfills at Upminster Hall | Old Upminster

Pingback: Upminster Hall: owners and buildings | Old Upminster