The following extract from Upminster: the Story of a Garden Suburb tells the story of WP Griggs & Co.’s purchase of the Upminster Hall Estate in 1906 and the early development of the Upminster Garden Suburb .

Lanes of Elm and Oak: Upminster, an Edwardian Garden Suburb

THE CLOSING YEARS of Queen Victoria’s reign were marked by a housing boom to cater for the rapidly-increasing population. Thousands of acres of countryside surrounding London gave way to serried ranks of almost identical red-brick terraced houses, typically unimaginative in layout with long, straight streets on a grid-iron pattern which met the minimum conditions for frontage and size set down in by-laws. Trees and hedgerows were rooted up and all traces of the rural past were obliterated as estates were rapidly developed by speculative builders to meet what they felt were the needs of the blossoming lower-middle classes — the clerks, shop workers, teachers, salesmen and others who played an increasingly important role in Victorian society. But by the end of the queen’s long reign there was increasing awareness and concern about the irreparable damage to the environment caused by this unplanned suburban growth. Many people were also starting to realise that the quality of life in the new suburbs left much to be desired. As The Times noted in 1904:

to surround London with acres of such streets is to produce a district of appalling monotony, ugliness and dullness. And every suburban extension makes existing suburbs less desirable … It is the more necessary, if possible, to redeem the suburb from meanness and squalor.

Another factor was at work: the rising hopes and aspirations of those middle-class suburban occupiers who could afford something better than their dull terrace and who wished to break away from rubbing shoulders with the working classes, from whose ranks many of them had emerged. In contrast to suburban housing, homes for the professional and upper middle classes were marked by their variety and style: there was clearly a need for new ideas on suburban development which would meet the lower middle classes’ aspirations and their ability to pay for a better type of house.

The concept which did most to meet these emerging needs was the garden city movement which had gained much attention and enthusiastic support since it came to the public eye with the publication in 1898 of Ebenezer Howard’s book Garden Cities of Tomorrow. Howard’s vision was for developments of quality housing on a grand scale set within surroundings which retained as much as possible of the characteristics of the countryside which they replaced. He saw the garden city as being self-contained, with industrial zones within walking distance of employees’ homes. Unlike many visionaries Howard lived to see his ideas put into practice: in 1903 almost 4,000 acres of land were acquired by the newly-established “Garden City Pioneer Company” at Letchworth in Hertfordshire where work started on housing laid out at low densities of no more than eight to the acre to designs by the architects Raymond Unwin and Barry Parker.

A smaller scale variant on the garden city was the Garden Suburb, based on Howard’s ideas for houses set within rural surroundings but without the need for a self-contained community with its own industries. Those as-yet undeveloped London outskirts, with easy rail access to the employment opportunities of the City, which had avoided the late-19th century developers’ attentions, were obviously ripe for development as garden suburbs.

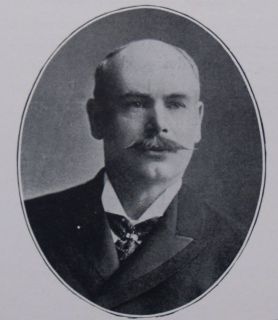

It was against this background that towards the end of September 1906 W P (Peter, later Sir Peter) Griggs announced his intention of laying out some 700 acres of the Upminster Hall Estate for building purposes in a development which “would preserve its healthy and rural condition and would attract a desirable class of people to Upminster”. In an interview with the Essex Times Griggs expanded on his proposals which were fully in keeping with the garden city and garden suburb ideals. There would be “no more than two or three residences per acre and many would have a larger area on which one could have 50 or 100 fruit trees and grow all vegetables.” Larger houses were planned on the north of the railway, while to the south of the line “quite apart from the residential portion, so as to preserve its quietude and peace”, it was proposed to locate “business premises and the smaller class of house, with the cottages”. The Building Committee of the Romford Rural District Council supported the proposal for a development which would “preserve the well-timbered and park-like appearance of the property, planting trees in the side-walks and giving spacious frontage and from 60 to 70 feet, with depths of about 300 feet”. Griggs & Co sought the Council’s advice on “a specification of road construction, suitable and adequate to the rural requirements of what would then become a garden suburb”.

The planned development was ambitious. In addition to the initial estates south of the railway, on the land which the Branfills had sought to develop 20 years previously, and the area north of the railway flanking the prestigious Hall Lane, Griggs planned to develop westwards to the River Ingrebourne and eastwards to the boundary with Cranham. A further phase of building would extend northwards on the west side of Hall Lane, as far as Upminster Court, continuing progressively beyond Williams’ property in a development which would have stretched from the Ingrebourne to the Cranham boundary in the north, running right past the Hall Lane junction with Bird Lane and beyond. If completed, this would have taken Upminster’s built area from the railway to past the current arterial road (A127), except for the land directly around Upminster Hall.

Peter Griggs was already a developer of some renown, ranking only behind Cameron Corbett in the development of Ilford and surrounding areas. By 1898 his firm, W P Griggs & Co Ltd, in which he was ably supported by William Garbutt Key, had acquired the 215 acre Cranbrook Park Estate, Ilford between the Cranbrook Road and the River Roding and had erected substantial, if monotonous, houses in streets bearing impressive names such as Kensington Gardens, De Vere Gardens, and Mayfair Avenue. A second Ilford estate, the Central Park Estate around Valentines Road, followed after 1900. The “CranbrookPark and Central Park Estates” in Ilford were publicised to be “without question the choicest positions in Ilford and surrounding districts. Substantially-built residences are being erected.” Griggs himself took residence at No. 7 The Drive, with his partner Key as his next door neighbour at No. 5 while at No. 9 lived the Rev Charles Vine, long-time minister of the Ilford Congregational Church at which Griggs worshipped fervently.

Published accounts of Griggs’ life record his birth in “humble surroundings in South Hackney” on 1 November 1853 and state that his father, John, died when Griggs was seven years old, leaving his mother, Martha, to bring up the family alone. Reportedly apprenticed to a Thames lighterman, later saving hard to buy his own barge, which he was forced to give up, Griggs saved to buy another and in time made enough money to allow him to leave the river. To what extent is this account true?

The birth entry for William Peter Griggs reveals a discrepancy with the published accounts. His birth took place at 123 Brick Lane, Bethnal Green on 1 November 1849 — four years earlier than the birth date Griggs later admitted to, and in a different place. He was the son of John Griggs, a cheesemonger of Buckinghamshire origins, and his wife Martha née Catt, with an older sister Martha and a younger brother Phillip. What then of his father’s premature death? The LondonPost Office Directories confirm John Griggs, cheesemonger at the Brick Lane address from 1850 to 1858, succeeded by Mrs Martha Griggs until 1878. The entry for John’s death, aged 52, on 30 September 1857, caused by chronic hepatitis, confirms that young William Peter was indeed seven at the time of his father’s death.

According to a published account Griggs “by dint of rigid economy managed to save sufficient to acquire a £500 vessel, paying £100 down and the remainder by instalments”. By his own account “at the age of 30 … I had made and lost a fortune. I determined to start again, and I recovered myself, although it took me years to do it”. The extensive records of the Company of Watermen & Lightermen confirm brief details of Griggs’ career as a lighterman on the River Thames. Bound as an apprentice for five years to William Gregory of Deptford in October 1869 at the relatively late age of 19, Griggs paid his dues to the Company as a working lighterman for ten years from 1874 to 1884. The Company’s registers of barge owners indeed confirm that, only a few years after becoming a fully fledged lighterman, Griggs had become the registered owner of a barge, soon adding another. The records also show that by 1878 when he was still only 28 years old, he had given up being a sole owner, taking instead a share in three barges as a joint owner, which he relinquished in 1885. This broadly confirms the published accounts and suggests that Griggs’ involvement with the lighterage trade ended around 1885.

However, the background to Griggs’ conversion from the lighterman and barge owner of 1884/85 to major housing developer in 1897 remain obscure, although an obituary suggested that he came to Ilford from Bexley in Kent around 1890. Before his major developments at Ilford it seems that he was involved with building works at Wanstead, Walthamstow and Leyton. But by all yardsticks he was the epitome of the “self-made man”, typical of the Victorian era, who by his own efforts had risen from lower middle-class surroundings to considerable wealth and social prominence — he was elected to Ilford Council in 1899 and to Essex County Council two years later. By the end of 1904 W P Griggs and Co had already contributed some 2,000 homes to Ilford’s development but he acknowledged that it had “been very difficult to keep things going. The firm has to give even more to people in the shape of improvements to induce them to buy.”

Griggs & Co’s proposed development of the Upminster Hall Estate found favour with the media: the Essex County Chronicle concluded that “if park land must be handed over to the builder ‘a garden suburb’ is much to be preferred to a London dormitory”. With the support from the local Council and such endorsement in the press the way was clear for Griggs to seal the purchase of the initial 150 acres of land on which the first stage of his estate was to grow. On 1 November 1906 he paid £20,000 to Capel Aylett Branfill and John Arthur Capel Branfill, trustees of the late Captain Benjamin Branfill, to acquire land extending 920 feet to the west side of Hall Lane north of the railway, shortly to be developed as Waldgrave (later spelt Waldegrave), Engayne, and later Ashburnham Gardens. Fields eastwards of Hall Lane were also acquired, to become Deyncourt, Courtenay and IngrebourneGardens, together with the 15 acres to the south of the railway down to Cranham Road on which Branfill had proposed to build and on which St Lawrence, Howard and Garbutt Roads were now to be built following similar plans. The agreement with the trustees prevented Griggs from building any house on Hall Lane “of less value than £400 prime cost”, no house was to be erected north of the railway for “less than £250 prime cost” while no timber could be cut down “except as might be necessary for the formation of roads or such as might be deemed by the District Council or other local authority to be dangerous”.

The first brick was laid just over two weeks later on 17 November 1906, with the earliest attentions being paid to the prestigious detached houses on Hall Lane and the south side of Waldegrave Gardens, to the designs of the Company’s architect Mr George Verlyck. Within six months Griggs’ publicity machine was in swing. By early May 1907 the national newspapers carried advertisements for houses on “a real garden suburb near London” where “choice residences of varied designs are being erected on this Picturesque Estate, on high ground with very large gardens”. Prices were from £395 to £1,145, with 999 years’ leases or freehold purchase available. The premium prices were reserved for a few exclusive detached properties on Hall Lane but in general the larger double-fronted four- and five-bedroom detached houses on Hall Lane and in the adjoining roads sold for between £750 and £900, while semi-detached houses north of the railway sold for between £350 and £500. In contrast the much smaller houses on St Lawrence and Howard Roads typically sold for between £230 to £240, with those on Cranham Road (Esdaile Terrace) for around £275.

For the practically minded Griggs extolled the virtues of the easy rail access, offering to provide rail timetables, while for the more romantically minded readers the advertisement quoted from Tennyson urging them:

To change our dark Queen City, all her realm

Of sound and smoke

For His clear heaven and these few lanes of elm

And whispering oak.

Griggs was ready to publicise his development in a big way. On 24 May 1907 a large party of newspaper reporters and others of influence gathered at Fenchurch Street Station where they were met by Griggs and his fellow director, Mr J W Thompson, MP for East Somerset. At Upminster the guests were able to witness the rapid progress of the past six months: between 20 and 30 “very imposing” detached villas “of commanding appearance” and other semi-detached properties were on view. The showpiece was perhaps Glen Caladh, (now 28 Hall Lane) to which W G Key had already moved from his Ilford home. Here the guests “had an opportunity of forming an idea of the value of these handsome dwellings in the garden suburb” and were entertained with a “capital luncheon”, followed by speeches by Griggs, Thompson, Dr V Rutherford, MP for Brentford and Mr Holland, Chairman of the Woolwich Building Society. Universally good publicity in the local and national newspapers followed. According to the Daily News Upminster was “one of the true beauty spots in an under-rated county” while the Grays and Tilbury Gazette described the houses as “modern certainly, but artistically modern”. The Civil Service Gazette recommended that “civil servants who contemplate living in the country should pay Upminster a visit” and felt that “it is not too much to say that the first garden suburb worthy of the name bids well to prove an unqualified success”.

Progress continued unabated. The Rural District Council deliberated in December 1906 about plans for the sewers to serve the estate, and the necessary loan of £450 from the Public Works Loan Commission was finally approved over six months later. Mr F C Thompson was appointed as the council’s contractor, starting work on 20 August 1907 and the sewer’s course under the railway to the sewage works at Puddle Dock, Cranham was complete by late September, ready for connection to the estate.

By the start of July 1907 the road surface of Waldegrave Gardens had been hardened and portions of the footpath spread with gravel, and a few weeks later the metalling of Hall Lane was under way. By early September the Company reported that they had “practically finished” making up Hall Lane, Waldegrave, Engayne and Deyncourt Gardens. The Council Surveyor had a different view: the road surface of Engayne Gardens was “rough, the kerbs not properly jointed … and no gas lamps and columns have been provided” while both sides of the other streets had not been “wholly built upon and all houses fully completed”. It was to be nearly 11 months before the Council were prepared to accept that the roads were nearing the stage where the Council would take over their maintenance. WaldegraveGardens came first – the six months period of maintenance by the Company running from July 1908 to January 1909 when the Council took it over as a public road – to be followed in May 1909 by lengths of Engayne, Deyncourt, and Courtenay Gardens. The Romford Recorder felt that “this speaks well for the progress that has been made by the owners of the garden suburb”. Not all housing developments in Upminster ran as smoothly as Griggs’ garden suburb development. A less than successful venture took place just across the border in Cranham where in early 1907 the Land Company, 68 Cheapside, EC1 initiated the sale by auction of plots on the “Cranham Park Estate”, around Moor Lane, CranhamGardens and Park Avenue. It was claimed that this development would not only appeal to the investor but “to the City Man or anyone else whose business is principally in the Metropolitan area but who desires to live in healthy country surroundings away from unending streets of bricks and mortar”. Although the Romford Rural Council had disallowed the scheme when it was submitted for approval in November 1907, in July 1908 the Council’s attention was drawn to the fact that streets had been laid out without permission. In December that year the Council agreed to take proceedings against the Land Company as they had laid out streets without complying with local by-laws. The following year the District Medical Officer of Health noted with concern in his annual report that houses had already been built and others “were being erected without proper water supply”; by 1911 he was able to report that the estate, which hitherto had depended “for its water supply upon a neighbouring private source” had at last been connected to the South Essex Water Company’s mains.

Meanwhile building work had also been proceeding rapidly from around 1906 on Griggs’ estate to the south of the railway, with the initial stretches of Howard and St Lawrence Roads being developed eastwards from Station Road by 1907. By July 1911 the developments of smaller houses on both sides of these long roads, some 170 yards of Howard Road and 270 yards of St Lawrence Road, were complete and six months later the Council accepted liability for their maintenance.

Griggs and Co’s plans for development continued to expand, adding the New Place estate in September 1909 and, in the summer of 1911, the unfinished Branfill Park Estate was added to their land bank, immediately initiating proposals for future development. In May 1912 Griggs completed the purchase of a further 36 acres of the Upminster Hall Estate, directly to the east of ClaremontGardens.

The census of April 1911 recorded some 2,468 inhabitants in Upminster, an increase of almost one thousand or 60% on the 1901 total of 1,468 individuals. There were 553 families compared to 323 ten years earlier, suggesting that this first stage of Upminster’s expansion had added around 230 houses, most in the four years since Griggs’ development started in 1906.

Where then had Upminster’s new residents come from? Large scale evidence is lacking but some indication of residents’ origins comes from the membership roll of the Upminster Congregational Church, which records details of those joining the church congregation and naming the church at which they had previously worshipped. This suggests that the largest group, headed by W G Key, had formerly lived in Ilford, possibly indicating that Griggs & Co had targeted the residents of their other main developments. Forest Gate provided the next largest group, with others moving from nearby areas such as East Ham, Walthamstow, Leytonstone and Woodford. From further afield in Essex a small group had moved from Westcliff and Southend, attracted no doubt by a quicker daily rail journey to the City, while there appears to be some truth the Civil Service Gazette‘s assertion that residents from “all the better-class districts of London” were showing interest: among further-flung areas represented were Norwood and Muswell Hill.

Evidence of occupations for residents on the Upminster Hall Estate comes from the parish register: the earliest mentioned include bank clerk, schoolmaster, engineer, civil servant, retired manufacturer, Trinity House pilot, printer and draper — almost without exception solidly middle class. This was reinforced by the names of the houses. In Hall Lane the detached houses were given distinctive names including, in addition to Key’s Glen Caladh, Daintree House, May Lodge, The Gables, The Croft, Broome Knowe; those named after trees such as The Pines, The Cedars, and The Elms; and those redolent of colonial origins, such as Kung Fah and Dilkusha. Houses on the Branfill Park Estate also bore grand titles such as Aldersmead, Valkyrie and Ellesmere in Champion Road and Ben Hilly and Lansdowne in Gaynes Road.

From Upminster: the Story of a Garden Suburb Tony Benton, with Albert Parish (self-published, 1996, revised & reprinted by Amberley Books, 2009, pages 22-31)

From Upminster: the Story of a Garden Suburb Tony Benton, with Albert Parish (self-published, 1996, revised & reprinted by Amberley Books, 2009, pages 22-31)

Available from Swan Books

Hello I have been sent to you by Simon Donoghue as he said you are the expert on Upminster. We have been doing my Husband’s family history and made a discovery that a John Haddon Attenborough lived at 32 Highview Gardens Upminster, I think it would have been with his family. I wonder if you have any information on this road, unfortunately like so many he never returned from WW1 he was KIA on 1 July 1916 (The Somme) he was promoted to Second Lieutenant. I am very pleased to say that my Husband’s Mother Joan Sach nee Attenborough told me about her Uncle that she lost in the Great War and I was able to find him whilst she was alive, and was able to show her a picture of where his memorial is, she did cry bless her.

Any information greatly received. As a footnote John Haddon’s brother George Urray Attenborough (my Mother in Law’s Father) actually owned Grove Farm South Ockendon, which I believe he sold Victor Maddon.

My great grandparents owned Grove Farm before it was sold to Victor Madden. I spent a lot of time with Uncle Urrey when I was young 🙂

I’ve emailed with further details but unfortunately, as 32 Highview Gardens wasn’t built until 1921 as John Haddon Attenborough died in 1916 he couldn’t have lived there or anywhere else in that road as building work only started in 1917 on number 2. So far I’ve drawn a blank.

Pingback: Going Up The Junction? | Old Upminster

Hi there! Someone in my Myspace group shared this website with us so I came to check it out. I’m definitely loving the information. I’m book-marking and will be tweeting this to my followers! Great blog and brilliant style and design.

Many thanks for your kind comments – just discovered this had been filtered into Spam folder! A new post is hopefully due to appear within the next 10-14 days, if not sooner.

Very descriptive blog, I liked that a great deal. Will there be

considered a part 2?

Pingback: Griggs Close, IG3

Pingback: Upminster Hall: manor and estate | Old Upminster

Good evening

I am trying to complete my family tree and I understand that my maternal grandmothers parents had a farm in upminster. Her name was Mary Helen Dawkins born 1910 she had sisters Ethel and Elizabeth (betts) she also had brothers. Not sure of her parents names that would have owned/ run the farm. Any help greatly appreciated

Kind regards

Julie Gaskin

Hi Julie. Can you email me please at tony-bemnton@ntlworld.com – was she Mary Helen Betts who married a Dawkins?

Good evening. I am trying to find out more about the history of a specific house placed in Deyncourt Gardens ( previous owners and original looks of the house). I have not been able to find many photos of the street from the time those houses were built, though. I was wondering if you could help me. The house number is 52 Deyncourt Gardens

Hi Katarina – email me on tony-benton@ntlworld.com

Pingback: Lily’s World | Old Upminster